Categories

Oak updates

7 July 2022Curriculum matters: Matt Hood’s keynote session at The Festival of Education

Matt Hood OBE

Chief Executive

At Wellington College on 7th July Matt took to the stage to speak in detail about why curriculum matters so much, and the system-wide challenges Oak will play a role in addressing in its future as an arms-length body.

I want to start by thanking the thousands of pupils, parents, teachers, school leaders, partner organisations, volunteers, civil servants, ministers and Oak staff members who brought their energy and expertise to this project.

Together they have created over 10,000 lessons across 24 subjects, including lessons for those who attend schools in the specialist sector. Pupils have completed just shy of 150 million Oak lessons.

Teachers have downloaded nearly 2.5 million quizzes, slides and worksheets, and given us over 6,000 pieces of feedback on how to make them even better.

Every week over 170,000 pupils and over 30,000 teachers still use Oak.

The lessons are accessible, including captions across all and British Sign Language across lessons for the youngest.

The lessons can also be auto-translated into 15 languages, including Ukrainian. And all for the annual cost of an average secondary school with the staff of an average primary school. It really is a living example of the best of our profession, and a testament to what we can do when we work together.

I believe what has been built, and the spirit in which it was built, is too precious to just label as ‘something we did in the pandemic’ – and for some time we’ve set about trying to find a long-term home and role for Oak. I’m excited that we’re now well into the process of transferring this national asset into public ownership by becoming an independent, arms-length body of the Department for Education.

As part of this work, it's proposed we’ll keep doing what we’re doing: being there in the event of any future disruption, supporting with cover, helping with lesson planning, providing catch up and homework. All of this, and anything else you might use us for, will remain an important part of our work and who we are.

But in addition, we’ve been tasked with turning our focus to supporting the system with curriculum expertise.

This new focus means that there is lots to think about. This presentation comes at a really pivotal point in the life of Oak National Academy and I’m excited to share some of that early thinking today.

Obviously, there is quite a lot of political change happening right now.

What I know about Oak is that we are at our best when we deliver in the face of rapidly-changing circumstances.

The decision to create an arms-length body has been made. We’re going to continue work delivering that, so I still want to lay out the thinking.

But it's worth me being clear that final decisions on the future scope and activities of the arms-length body are not yet made.

Over the last week, the Department for Education has held a series of webinars laying out some current proposals, seeking feedback ahead of final decisions.

What I’m sharing with you today is in line with those proposals – so I, too, am keen to get your thoughts and feedback afterwards.

Oak has always listened and responded to teachers; that should be how our future is shaped too.

Curriculum, pedagogy and assessment

I wrote an article in 2018 where I argued that England was having the best conversation about education in the world. Ever the optimist, I stand by it today.

That conversation has been fueled by teachers and school leaders taking control of their profession, talking to each other, and making ever-better bets about what will improve outcomes and close gaps in their classrooms – built on an ever-improving body of evidence.

Of course, the pandemic has reminded us of those critically important factors beyond teachers’ control that influence pupil outcomes and the attainment gap. As a society we neglect these at our peril. But when it comes to what is in our control, it’s my strong view that we’re making excellent progress towards the goal of becoming the best at getting better.

We’re increasingly putting to bed poorly-evidenced approaches that dominated my own teacher training and early career, and we’re replacing it with a laser focus on education’s holy trinity of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, wrapped in a calm, safe environment, with excellent pastoral care. The evidence is clear: this is a great bet and where our focus should be.

The significant and welcome professional development reform programme has put rocket boosters under this work.

Curriculum: a vital lever

Amongst education’s holy trinity, it’s the curriculum that has had renewed focus of late. And whilst we must avoid lurching from one branch of the trinity to another - pedagogy and assessment matter too - this renewed focus, precisely because curriculum should be our starting point, has been welcome.

We know that pupils who experience success when learning are likely to spend more and more time doing it, getting better and better, while those who find it more difficult come to believe that it is not for them and do less of it (the Matthew Effect).

Applied to the curriculum, it means the more a pupil knows, the more easily they can make sense of new knowledge, contextualise it for themselves, and go on to develop a sophisticated understanding of the subject.

It is therefore also a matter of social justice. Curriculum is a vital lever as we seek to reverse the tidal wave of a widening attainment gap, washed in by the pandemic.

And as I’ve already mentioned the educations’ holy trinity and one of the gospels, it now seems appropriate to quote one of our Saints: Professor Dylan Wiliams argues that “the best curricula generate at least 25% more learning than the worst, irrespective of teacher quality.”

It’s clear we need this focus so every child has access to a high-quality curriculum.

This renewed focus has had a marked impact at the secondary school I Chair in Morecambe, where there have been big leaps forward in the way in which we think about what we teach and in what order.

What I find most powerful about our progress is seeing teachers hypothesise that the roots of a particular student misconception might be found in how we have chosen and sequenced the actual content, rather than just how we are teaching it - which always used to be the primary hypothesis for student misconceptions.

I know what’s happening at Bay Leadership Academy in Morecambe is a story that is being replicated in many schools and school trusts across the country.

But even ‘happening in lots of places’ has never been, and will never be, good enough for our profession. That’s because we don’t believe that we are only responsible for our pupils; we believe we have a responsibility to help each other in the service of all pupils. If Oak proves anything, it’s that this belief is alive and well.

And we know that this progress in curriculum quality isn’t happening absolutely everywhere.

The progress in my secondary school hasn’t yet been replicated in my primary school up the road in Carlisle. With more support, we’ll make that progress faster.

This situation is not uncommon. Ofsted’s research found challenges on curriculum knowledge(1) and concerns about curriculum planning(2). Ofsted’s subject reviews have had a huge amount of interest, so there is clearly a strong appetite for some help and guidance on subject-specific curriculum thinking.

Nor is it uncommon for there to be variation within schools or school trusts. I don’t know a single CEO or headteacher who thinks that they have nailed the curriculum for every subject, in every key stage.

And it’s not surprising. Why? Because this stuff is really hard.

You need time and expertise

Designing and developing a curriculum is both complex and time-consuming at every level - from deciding whether or not to teach perimeter and area separately, right through to identifying the best images and graphs for a lesson on glaciers.

You first need time upfront. It’s not something you can do with 30 minutes between lessons. Experienced teachers need to sit, think and collaborate. Any teacher will tell you finding that kind of time in a school day is like panning for gold.

Once you have designed your curriculum, you then need implementation time, and even when implemented, the curriculum doesn’t stand still.

You need to have time in your back pocket because feedback loops will result in necessary or desired changes as you see what works and what doesn’t with your pupils. And when the curriculum changes, all the lesson plans and resources need to be updated in line with it.

Second, you need expertise. Expertise here comes in two forms. First is the deep subject knowledge required to build a great curriculum. Second is a deep understanding of how pupils learn, which translates into the careful selection and sequencing of knowledge and skills.

These two areas of expertise are interlinked. How you sequence a curriculum and build knowledge will, in part, depend on the specifics of your subject. An English teacher may tell you, for example, it's better to sequence knowledge around a theme of tragedy, comparing and building between different authors rather than simply focusing on Shakespeare and the tragedy found in King Lear or Macbeth.

No one teacher, however experienced or expert, can do this right across all content within a subject and all key stages. A team is required.

Expertise is dispersed

Without a team it is impossible to knit together subjects over time, to make the most of those cross-curricular connections. It is these connections that ensure that individual components, distributed across subjects, can come together into more complex composites.

This team of experts exists. They’re working up and down the country. As teachers right across our 24,000 or so schools. In our brilliant collection of subject associations. Within publishers creating content for teachers.

But it’s a dispersed team. It’s not one that every teacher can easily tap into, learn from, or draw down on.

We have to change that - to make it so every teacher has the best curriculum thinking, the deepest subject expertise, and the smartest learning design at their fingertips.

If we believe that curriculum matters; if we believe that creating an excellent curriculum that knits together every subject and key stage matters; if we believe all pupils marvelling at the best of what has been thought, said, sung, danced and painted matters; and if we believe it is hard to achieve because it takes more time and curriculum expertise than many schools have access to; then I think it follows that we need to do three things.

1. Bust a myth

Let's start with addressing the myth: that, as a profession, we have to choose between teacher and school autonomy and teacher workload and wellbeing. This just isn’t true.

It is perfectly possible for teachers to avoid creating every aspect of a curriculum from scratch, along with all the elements of every lesson - which otherwise often results in crippling teacher workload, whilst rejecting top-down centralisation, with no teacher agency and diminishing expertise.

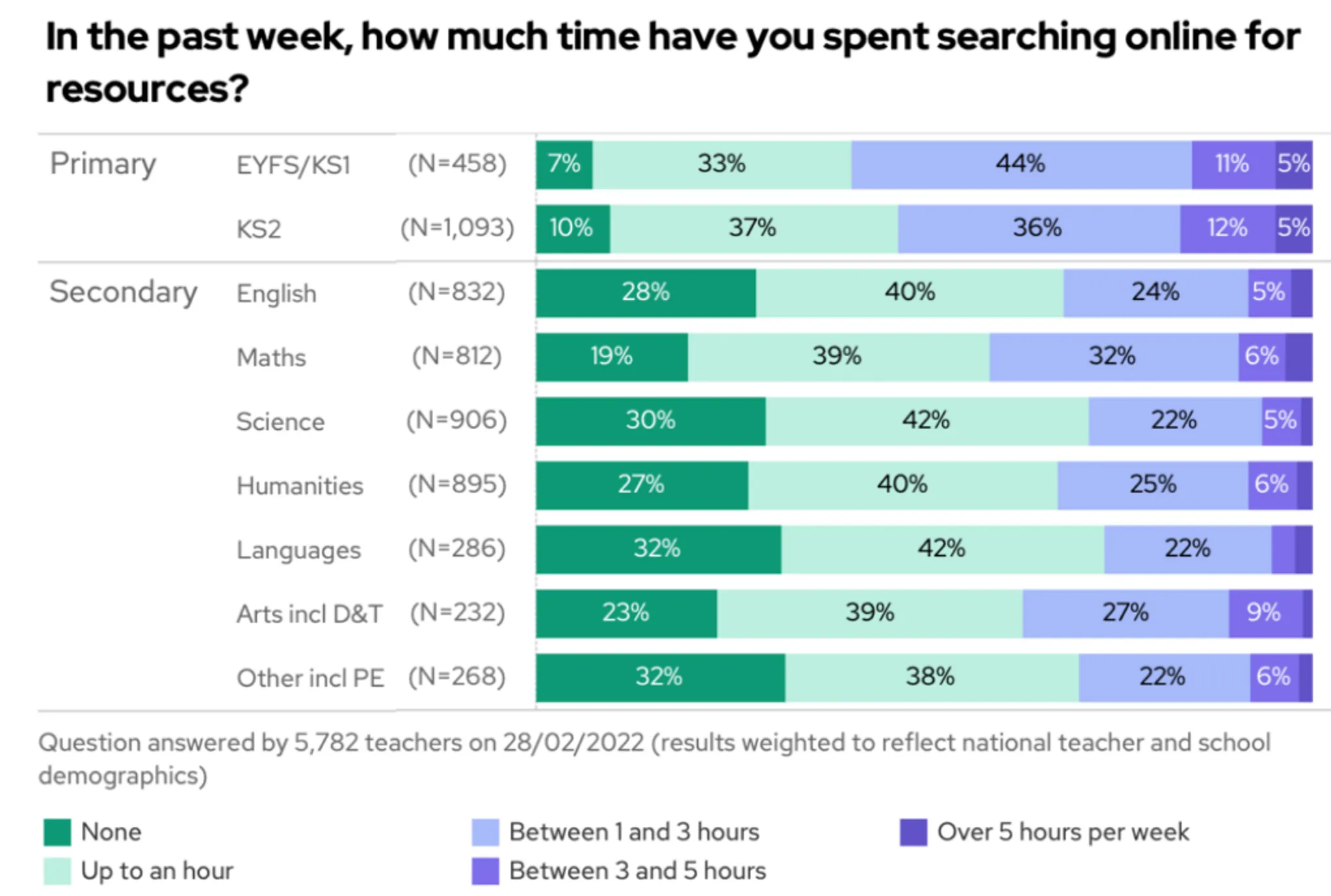

And if we’re in any doubt about this workload burden, it’s worth remembering that teachers spend a considerable amount of time searching for lesson materials. The majority of primary teachers spend between one to five hours online each week looking for resources, and almost half of them say they plan a lot of lessons from scratch.

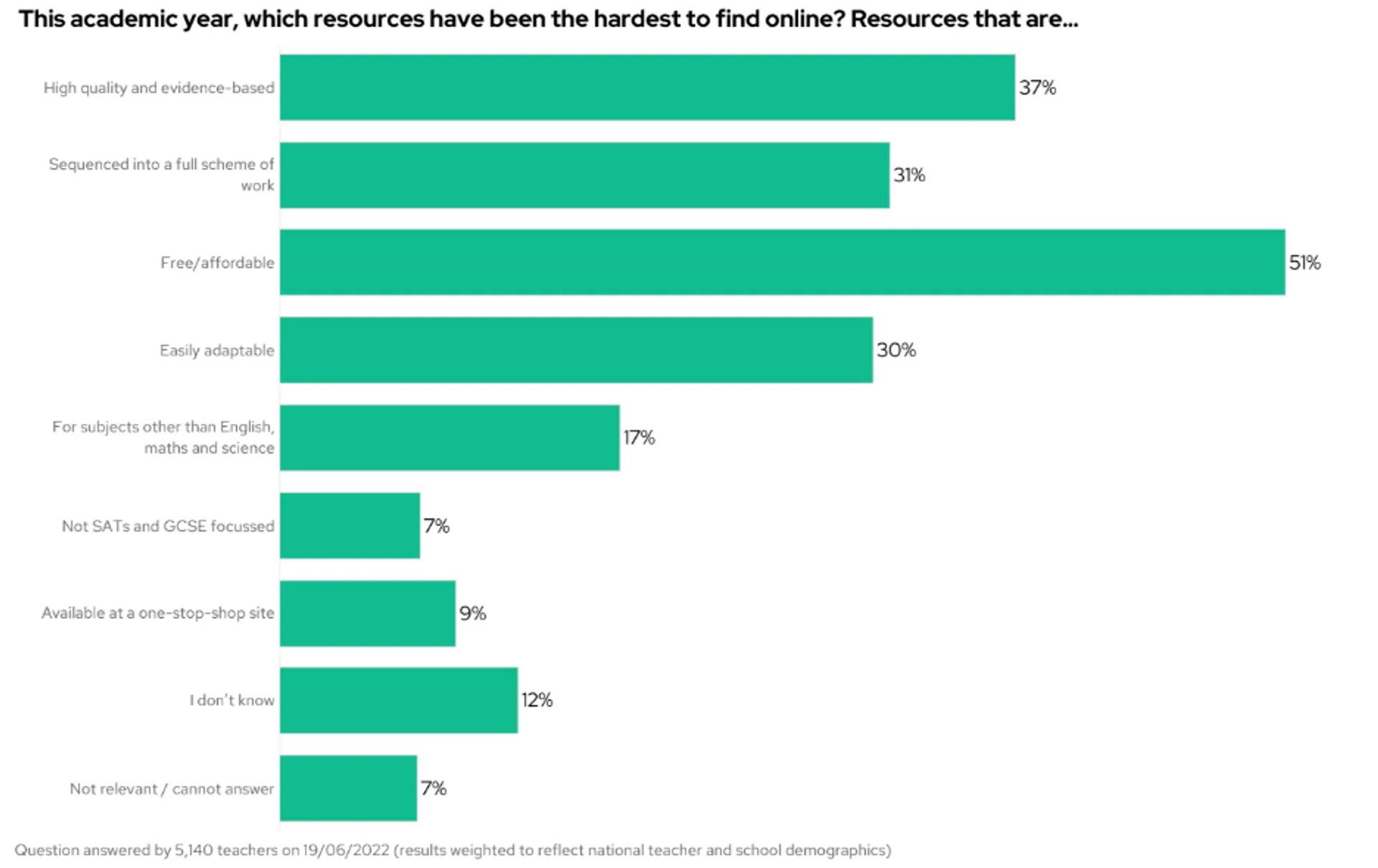

We’ve just conducted more new research on this. We asked teachers, via Teacher Tapp, what it was particularly difficult to find online. Over half said they struggled with free or affordable resources.

Over a third said it was high-quality, evidence-based resources that were a challenge. Their next greatest challenge was resources sequenced into a full scheme of work.

Teachers working in the most deprived areas, or those newest to the profession, found searching for these resources harder still(3).

Teachers will always need to adapt, to contextualise, to tailor to their pupils. But they need not always spend so much precious time if they don’t want or need to.

We should trust and support teachers to make informed decisions, so they know when drawing on shared resources might be helpful, and when, and what, they need to design themselves.

It is particularly frustrating when it’s presented as a zero-sum game: that what teachers might gain by accessing shared expertise, they’ll lose in autonomy.

This isn’t how teachers see it themselves. The data shows day-to-day teachers are happy to draw on a wide range of tools and resources from others. 92% of them use more than one major online resource provider(4).

And as I’ll explain, seeing others’ work and seeing models can inspire and increase expertise.

This polarisation - complete autonomy vs total centralisation - is unhelpful. It risks stymying sector-wide attempts to find and share the best curriculum expertise in the system.

2. Create a new national collaboration to share models

The second thing we need to do is to establish a new national collaboration to create more curriculum models.

At Oak, asking teachers what they want and need from us is the start of everything that we do.

That list I presented earlier - the 10,000 lessons, zero-rating, British Sign Language, Ukrainian translation – alongside all of the ‘day-to-day things’, like resizing our downloadable quizzes to keep photocopying costs down – all came about because we asked teachers what they wanted and needed and then built from there.

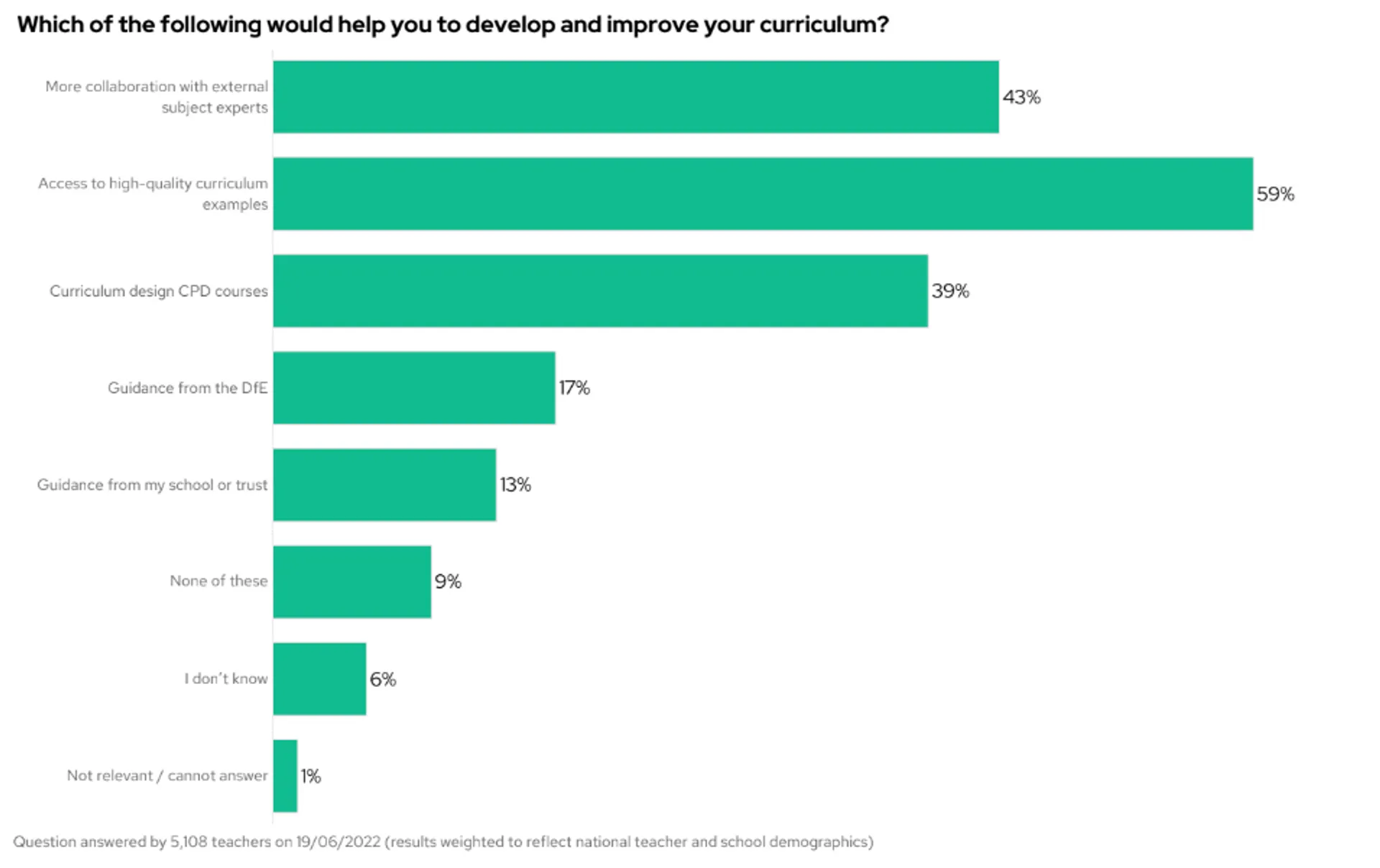

The curriculum question is no different, and so we’ve asked again. New research we commissioned, again via TeacherTapp, tells us that teachers want two things to support them with their curriculum work: almost two-thirds said they wanted to see good examples, and just under half wanted to collaborate with experts from outside of their school(5).

It’s not just teachers telling us that this is what they need that gives us confidence that we’re on solid ground. The literature and our experience points us there too.

We know that seeing good examples, or models, is a good bet. We know that they aid learning for both pupils and adults, and we know that teachers often find it hard to find them.

In the evaluation of Oak carried out by ImpactEd last year 56% of our teachers told us that we’d helped them improve their curriculum thinking and the conversations they have about curriculum in their school.

And as we know, it’s not just that collaboration is a good bet. It’s essential because our experts are distributed far and wide across the system.

3. Put some clear guardrails in place

The third and final thing that we need to do is to establish a number of guard rails that prevent any unhelpful mutations of this work - either now or in the future.

That’s why it will be written into our founding documents that Oak National Academy will always be:

- independent of government - so that Oak’s roots as by teachers, for teachers, are protected, and our work isn’t buffeted by the political winds of the day;

- optional - because it’s up to schools to always decide what their curriculum will look like;

- adaptable - because no model can suit every teacher in every context;

- free - because access to this work shouldn’t be based on who can afford to pay.

Independent. Optional. Adaptable. Free.

As well as these fundamentals of how Oak will operate, I think it’s important to be crystal clear on what it won’t look like. Ever the teacher, I want to give you a non-example.

The solution will not be found in:

- a narrative where teachers and school leaders are told we need to do this because we’re not good enough. We need a narrative of doing this because we know we can be even better - that’s what being the best at getting better means;

- something that is top-down, small tent, inflexible or mandatory;

- something that is rushed, ill-thought through and not by teachers for teachers.

The proposal

So this is where we are. Creating a great curriculum requires time, deep subject knowledge, and design expertise. It’s all there in the system. It’s happening in schools, trusts, subject associations, and publishers.

But it’s dispersed, hard to share and access, and still developing. We can’t hand on heart say this is consistent across every subject area and accessible to every school and every teacher (yet).

But that’s got to be the goal. For us truly to deliver better pupil outcomes and to close gaps, we need it in every school.

We are therefore laying out a proposal to deliver on this. As I say, this is currently out for feedback before any final decisions are taken.

The proposal is:

- An independent organisation, with teachers on its board

- Working with a diverse range of experts to assess the evidence, and agree rigorous quality standards, specific for each subject

- Identifying brilliant models and expertise from across the system to create curriculum maps, lesson materials (such as slides, quizzes and worksheets), and video lessons

- Supporting a broad range of subjects, with the first tranche being in English, Maths, Science, Geography, History and RE

- Doing this through an open and collaborative approach - likely via an open procurement from Autumn 2022

- Consistently listen to teachers - including road testing resources in schools before iterating and improving them

We then envisage schools and teachers using the resources in a variety of ways:

- To support curriculum and lesson planning

- To support the development of new and early career teachers

- For homework, tutoring or catch up

- Or, to have a remote-education contingency ready, should God forbid, we ever need it again.

Conclusion

Getting this approach right means that Oak must only ever be seen as a starting, and never an end, point.

Schools and teachers know their pupils best. They rightly feel a great responsibility towards them. Planning their curriculum and lessons is a vital and valued part of being a teacher.

Schools and teachers will, and must, continue to think deeply and carefully about what is best for them, their pupils, and their context. Choosing if and how they use Oak, just as they do now with a range of other support, tools and resources.

And they will, and must, consider how this is brought to life. As John Tomsett said recently, “Whatever the scheme [of work] is, teachers have to be able to make it their own. Children have got to learn, know, understand and apply this content. That depends on the pedagogy of the teacher to make it interesting for them.”

But we know teachers want support.

They’re struggling to find good-quality, sequenced, affordable resources. Our research shows it.

They want more examples of curricula, and access to external experts to help.

So we intend to bust this myth. You can protect autonomy whilst tackling one of the greatest causes of crippling workload.

This new national collaboration, sharing the expertise currently spread across our system; putting it on tap for every school in the country. Access to quality lessons, resources and models.

But it will be done with important guardrails in place: Independent. Optional. Adaptable. Free.

We want to hear from you

Before I finish, I just want to make one final request.

Just like in April 2020, this only works if we all lean in. So if you’ve been reading and thinking, ‘we’ve been working hard on our curriculum’ or ‘we’ve got a great sequence and set of resources’ – brilliant. We want to hear from you.

Whether it's in one subject or spanning many. Whether you’re a big organisation, or a small standalone school. I believe there is so much great work in the system.

Our role is to help to share it. And whatever you put in, I know we’ll all get more out if we all work together.

So talk to us. Help us shape this. Ultimately, it will be pupils up and down the country who benefit.

Footnotes

(1) Amanda Spielman, “Recent Primary and Secondary Curriculum Research”, in HMCI’s commentaries, (Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (OFSTED), 2017), (p. 3)

(2) ‘Education inspection framework: overview of research’ (January 2019), p.6, Ofsted

(3) Oak survey conducted via Teacher Tapp, 5,140 respondents, June 2022

(4) Based on survey with 629 teachers, asked about their use of BBC Bitesize, Twinkl, TES, Seneca and Oak National Academy over the past 6 months (March 2022)

(5) Oak survey conducted via Teacher Tapp, 5108 respondents, June 2022